|

The Home Vaughn Picked Up for a Song

By JESSYCA GAVER

RADIO-TV MIRROR

July 1952

"Comfortable

American" is the Monroe description of their home and family

ON

A CERTAIN U-shaped street in a certain Boston suburb, there's a house as

pretty as a melody-- a harmonious blending of red and black brick, based on a

Georgian colonial theme, with rhythm in every line. And why shouldn't it look

like lovely music? It's the happy home of Vaughn Monroe, his pretty wife,

Marian, and their two daughters, Candy and Christy.

"I picked it up for a

song, " quips the star of NBC's Saturday night Vaughn Monroe show.

"One that had to sell a

million records first!" Marian chimes in, completing the little family joke they

use to "explain" the special treasures Vaughn's well-loved voice has brought

them.

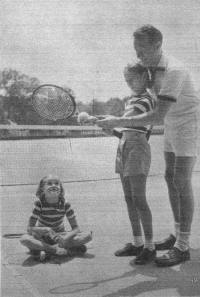

When the singing

bandleader isn't touring with his show, or making a movie out Hollywood way, a

typical summer day will find him back of the house in New Weston, Massachusetts.

He'll be playing tennis with his daughters on one of the two courts beyond the

arch of arborvitae. Or spraying his prized apple trees, while some of Chris's

and Candy's friends join them at the kiddy gym and swings Vaughn set up. Or

romping with Penny, the family's large brown-and-white shepherd collie, with an

occasional longing look at the almost-private golf course which belongs to a

club but closely adjoins the Monroes' 33,000 square feet of lawn.

"If their eighteenth

hole weren't so close to our dining-room window," laughs Marian, "I wonder if

Vaughn would be so eager to hurry home every moment he's not working!"

For a last-minute

inspection, she glances around the patio--which Vaughn built of flagstone,

complete with barbecue equipment--then hurries indoors to see, quite literally

"what's cooking." They're expecting company for dinner, and the beef is roasting

fragrantly. The Monroes don't have as many chances for home entertaining as

they'd like, so when Vaughn's there they make an occasion of it.

Actually, practically

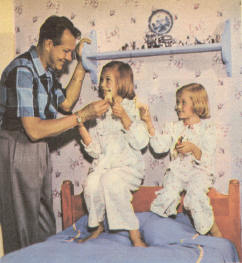

anything is the occasion for a party with the Monroes, complete with paper

cloth, fancy decorations and gifts from the girls. Candy (short for Candace),

ten, and Christy (short for Christina), seven, are allowed fifty cents each for

such gifts and shop diligently in the local five-and-dime for the special

something they always select. One Father's Day, Candy gave Vaughn a leatherette

pad with pencil attached--a pointed reminder of the way he yells for pad and

pencil when he's on the phone. Chris, knowing how her father likes roasted ears

of corn with his barbecues, gave him a pair of corn holders. Even four-footed

Penny comes in for her fifty cents' worth, such as a new kind of soap the girls

were told would do wonders in keeping flies away from her sensitive nose.

All the Monroes are

great on sharing--gifts, hobbies, jokes--and their house reveals it clearly.

Everything in it is a key to the individuality of each member but also to their

community of interests. An open-front cabinet in the living room holds the

lovely pieces of antique china Marian has collected in their travels, and the

dining room has the many silver pieces she's gathered. In the children's room

are the china horses and dogs the girls are accumulating--Vaughn always buys one

for each on his various trips--and in the master's den are the guns he has found

in out-of-the-way shops.

Downstairs in the

playroom are assorted curios bought by the entire family in its travels, as well

as the girls' record collection. Even the sides of the stairway leading down to

the basement are covered with framed mementos of Vaughn's career--the first

sheet music he ever recorded, covers of the first trade magazines which

mentioned him, all the landmarks of this progress which could be kept in

permanent form--the family calls it "Monroe's Alley."

Because the children are

being raised as average young girls, they are allowed a fair amount of freedom

of expression. They joke about their parents' foibles much as Vaughn and Marian

kid them--and each other--about some of their traits. Conversation is usually

lighthearted banter. Vaughn says the reason Marian loves him is because he shows

such proper appreciation for her cooking . She says it's his absent-mindedness

which keeps her permanently his slave, and she adores it. And they both say the

only way to describe their household decorating scheme is "comfortable

American!"

Marian insists that the

entire main floor is a monotone of gray, but actually it's highlighted with many

flashes of color and the gray tones themselves are blended and contrasted with

amazing variety. There is [line missing] wall on all the floors except the

kitchen and breakfast nook, gray wallpaper and pink ceilings in both the hallway

and the thirty-foot living room, where the gray slipcovers are trimmed with

coral. In the dining room, it's a gunmetal ceiling and gunmetal wallpaper with

flowery splashes of yellow and red, while the eighteenth-century mahogany

furniture has chair seats of hunter green leather.

In the breakfast nook,

gray is the background of a splashy country-style wall paper picturing green

trees and orange carts as color relief for the ebony-finished table and chairs

painted by Marian and Vaughn. Even a small powder room goes gray in effect with

silver gazelles on lipstick-red wallpaper. The only room on the main floor which

entirely eliminates the gray motif is the big kitchen, which is truly colorful

with its yellow tile walls, brick-red ceiling and matching linoleum.

When

the Monroes moved into the house, in 1948, they discarded all the old kitchen

equipment and put in everything electrical. But more noticeable than the

gleaming cabinets--or even the long counter running across one wall for quick

snacks--is a huge blackboard facing the inside doorway. There all grocery

orders, day-by-day reminders, phone calls and loving messages are noted. The

children particularly like it for rainy-day drawing. And who is the main subject

of their art work? Not Vaughn--their beautiful dog, Penny!

There

are wood-burning fireplaces in all the main rooms, including the master bedroom

upstairs. Above the one in the living room are two oil paintings of the

children, done when each was a year and a half old. Above the one in the master

bedroom hangs a large photograph of Vaughn and his favorite cigarette. Here

Marian has acceded to masculine taste by having the walls papered in white with

a blue spruce design, and blue carpeting on the floor. There

are wood-burning fireplaces in all the main rooms, including the master bedroom

upstairs. Above the one in the living room are two oil paintings of the

children, done when each was a year and a half old. Above the one in the master

bedroom hangs a large photograph of Vaughn and his favorite cigarette. Here

Marian has acceded to masculine taste by having the walls papered in white with

a blue spruce design, and blue carpeting on the floor.

"We aren't waiting until

the girls have romances to be relegated to the back parlor," Vaughn laughs,

pointing to the furniture arranged in front of the upstairs fireplace.

"You be we aren't!"

Marian agrees. "We decided that a love seat . . ." here Vaughn interrupts to

point out that it's large enough to actually seat two, "an upholstered

chair with ottoman and a coffee table would make a good spot to run to when

Candy and Chris start entertaining their beaux."

"But it gets used now,"

Vaughn explains. "You should see how many cold winter mornings the girls plug in

the electric coffee maker and bring up the toaster and fixings for a light

breakfast, so we can talk about the night or week I've been away. It sure beats

getting up early to eat downstairs."

When Marian and Vaughn

talk about the girls, it's easy to see they consider the long hard years behind

them well worth the struggle. Marian, as Vaughn's high school sweetheart, shared

all his struggles.

Born in Akron, Ohio, on

October 7, 1911, Vaughn finally settled in Jeannette, Pennsylvania, where Marian

lived. For quite a while he veered between trumpet playing and vocal work,

finally gave up the idea of concert singing to work with orchestras. In addition

to his trumpet playing, he served as driver of the instrument truck and

treasurer of the band. Finally, a couple of music business greats, Jack Marshard

and Willard Alexander--the former is now a partner with Vaughn in all his

enterprises, the latter is the present band's booking manger--decided that

Vaughn could be a singing bandleader personality and the present Monroe

organization was born, with results we all know so well.

From 1940 until 1945,

things were touch and go. Vaughn's weekly income was small and Marian, not

married too long, suddenly found herself traveling with the band in the capacity

of bookkeeper and general assistant. Then without warning, RCA Victor had Vaughn

record "There, I've Said It Again," and with nobody quite understanding why, it

became a national sensation, selling a million and a quarter discs. He followed

this with many other hits--the most recent, "Tenderly," "Mountain Laurel" and

"Lady Love."

Vaughn is the first to

insist that Marian's fortitude has been his strength. Marian is no shy little

wallflower hiding behind her big man. She's just a couple of inches shorter than

Vaughn, with a slender figure. She wears clothes well--preferring casual

ones--but her own grooming takes second place to worries about him and the

children. She often knits herself dresses that other women envy, although she

limits the use of their sewing machine to curtains and draperies for the house,

feeling her knack with a needle is strictly on the knitting side. Vaughn's many

slip-over sweaters and matching socks are products of Marian's industry during

train, bus and plane rides; and the children boast a supply of sweaters as

varied as their father's repertoire of songs.

What might make another

man sensitive is amusing to Vaughn. His inability to manage his personal

finances, for one thing. Marian kids him about the time he and his co-pilot flew

in Vaughn's private airplane to New York and had to wait at the field until

Marian arrived with the seventeen-dollar landing fee. Vaughn gets a sizable

allowance, but often forgets to take it with him, or lends it to someone else.

One time on the road he needed a check cashed, walked into a bar and showed his

identification. Unfortunately, he needed a shave and was wearing his oldest

clothes, as he usually does while driving. The bartender said: "Aw right. If

you're Vaughn Monroe, sing 'Ballerina,' brother." Vaughn warbled a few notes.

Then the bartender put a nickel in the jukebox. The same vocal tones came out.

Without another word, he cashed Vaughn's check. For once, Vaughn didn't mind

having to sing for his supper. Without that money, he'd have had a tough time

eating along the road.

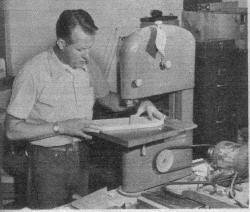

Vaughn has a number of

hobbies--pipe collecting, photography, motorcycling, flying--but samples of his

greatest are little seen at home. That's his wood-working, for when he does his

cabinet-making, it's usually as a present for a friend. What cabinets and such

Marian needs often can't wait for Vaughn's free time, so they're bought or made

elsewhere. One thing he did manage, however, was to build the inset cabinets in

the basement playroom, which not only double as seats but hold all the toys or

equipment used for indoor recreation.

The

basement room where Vaughn does his wood-working has an invisible keep-out sign

for everyone, except by special invitation. In it is as much equipment as you'd

find in the finest cabinet shop anywhere--a bulwark, Marina claims, against the

time when Vaughn may no longer care to sing or go on band-tooting one-night

stands. Vaughn's delight in new equipment for the shop, however, sometimes takes

comical turns. Marian recalls the time she asked Vaughn to sharpen a pencil for

her. Instead of using something easy, he insisted on demonstrating how this

could be accomplished with this newest lathe. Two boxes of pencils later, he

triumphantly demonstrated a perfect point. The

basement room where Vaughn does his wood-working has an invisible keep-out sign

for everyone, except by special invitation. In it is as much equipment as you'd

find in the finest cabinet shop anywhere--a bulwark, Marina claims, against the

time when Vaughn may no longer care to sing or go on band-tooting one-night

stands. Vaughn's delight in new equipment for the shop, however, sometimes takes

comical turns. Marian recalls the time she asked Vaughn to sharpen a pencil for

her. Instead of using something easy, he insisted on demonstrating how this

could be accomplished with this newest lathe. Two boxes of pencils later, he

triumphantly demonstrated a perfect point.

The two girls attend

Tenacre school in Wellesley, a primary school which is part of the Dana Hall

School. A school bus calls for them at eight each morning--with Marian to see

them off. This is because Candy will eat a good breakfast without supervision,

but Christy likes to be coaxed.

Marian's idea of delight

has nothing to do with food. It's the chance to slip on one of the many

negligees Vaughn has personally selected for her on his travels. He feels

slighted if she doesn't wear his gifts, so she makes sure to have a different

one on each time they can spend an evening alone. She wishes his memory were as

good when it comes to putting on the clothes he should wear for an

evening on the bandstand. Usually she packs a suitcase for him, but one

particular evening he dressed to take her to dinner, then brought her home early

and she decided that the outfit he was wearing was fine for his band assignment

that night, at a school dance not too many miles away. She kissed him good night

and went upstairs. Coming down a few moments later, she noticed his entire

outfit draped on a living-room chair. He had absent-mindedly changed into his

driving clothes and forgotten to pack the other things. She had to get a "ham"

operator a short-wave sending set to broadcast an appeal to Vaughn to please

come home for his clothes. Luckily, the set in the car was working and Vaughn

heard the message in time.

One

thing Vaughn never forgets, however, is the family. They do many things together

such as ice-skating and skiing in the winter, tennis and barbecuing and rides on

his motorcycle in the summer. He manages to get in a round of golf once a week,

as a rule, and they have musical family evenings when he's not on the road. The

children are his special delight, mainly because they are each so individual.

Christina, a true blonde, looks like an angel--but acts like a fiend, her mother

observes. Vaughn adds, "She looks like me, so I don't know where the angel part

comes in . . ." Candace resembles her mother, with ash-blond hair and what

Marian describes as the stubbornness and determination of her mom and the charm

of her pop. This shuts up Vaughn's jibes entirely. He insists if there are any

wings around they're not on Pop--they're on Mom! One

thing Vaughn never forgets, however, is the family. They do many things together

such as ice-skating and skiing in the winter, tennis and barbecuing and rides on

his motorcycle in the summer. He manages to get in a round of golf once a week,

as a rule, and they have musical family evenings when he's not on the road. The

children are his special delight, mainly because they are each so individual.

Christina, a true blonde, looks like an angel--but acts like a fiend, her mother

observes. Vaughn adds, "She looks like me, so I don't know where the angel part

comes in . . ." Candace resembles her mother, with ash-blond hair and what

Marian describes as the stubbornness and determination of her mom and the charm

of her pop. This shuts up Vaughn's jibes entirely. He insists if there are any

wings around they're not on Pop--they're on Mom!

Give the girls a chance

to be around Vaughn and they're in seventh heaven. He'll never forget how long

Candy waited to be taken to the The Meadows, the restaurant Vaughn owns in

Framingham, Massachusetts, to dance with her father after dinner. The night he

finally took her, some of her dessert accidentally fell in her lap. She was so

ashamed of her spoiled dress that she insisted on going home without the dance.

She didn't want to disgrace Daddy.

This business of being

children of a famous bandleader has in no way gone to the girls' heads, however.

Marian and Vaughn have explained to them that singing and leading a band are

jobs, just like the jobs their freinds' fathers have. It's taught them to

respect Vaughn as a hard worker, but not to boast about him to improve their own

social positions.

Any visit with the

Vaughn Monroes is filled with their reminiscences, their family jokes and their

closeness. To his wife and daughters, Vaughn isn't just a man who's built up a

two-million-dollar business around himself. Even if he were still only a

trumpet-tootling musician, he'd have "arrived" as far as his family's concerned.

Because to them--and to everyone who's met him--there's only one way to describe

Monroe . . .he's simply Vaughnderful!

|