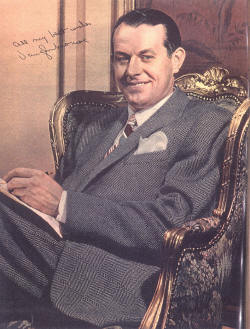

Revealing the life

and romance of the popular singer and band leader

MY STORY might have been quite different if it hadn't been for a

boy who gave me a trumpet. His name was Jack Willard, and both of us lived in

Kent, Ohio. One day he said to me, "Vaughn, I got an old trumpet at home that

belongs to my grandfather. They want me to play it, but I don't. If you want the

horn, you can have it."

MY STORY might have been quite different if it hadn't been for a

boy who gave me a trumpet. His name was Jack Willard, and both of us lived in

Kent, Ohio. One day he said to me, "Vaughn, I got an old trumpet at home that

belongs to my grandfather. They want me to play it, but I don't. If you want the

horn, you can have it."

Something for nothing you don't often refuse, so I took the

trumpet and liked the shine of it. I brought it home and told my mother I was

going to play it. I was all of ten then. "Honey," Mom said, "you can't play that

thing. The neighbors will object." I assured her they wouldn't. "Yes, honey,

they will," Mom said, and closed the argument. Or so she thought.

Next day I lugged home a book of trumpet exercises. "Mom," I

said, "you owe Professor Grace three dollars and a half. I got myself a

teacher." The professor was our local music master. Mom is a soft-hearted

person. She gave in, but she warned me I would have to practice in the cellar. I

went at my trumpet with surprising industry, for in three months I learned

enough to render-- that's probably the correct word-- a solo at a Kent high

school affair.

I think the zeal I showed must have come from a wish to assert

myself, for though I was tall and husky, I was often squelched by the kids I ran

around with. When I was six, the gang dumped me into a barrel of green paint. It

was two months before the last of the color wore off. Another time a boy in my

neighborhood decided I was a sissy because I wore Eton suits. I bore the

indignity but my father was outraged. "You teach that boy not to call you

names," he commanded, "or I'll switch you." So the next time the kid yelled

"Sissy!" I went at him. The result was sad for me. An aunt of mine watched the

battle and wrung her hands as she saw her nephew beaten up. When things got too

tough, she pulled me out.

Maybe I was just a happy child too content to be looking for

trouble. I was born of parents who were devoted to each other, and who made a

loving home for me and my brother Bill. I was born in Akron, Ohio, one festive

Saturday afternoon when most Akronites were out at the Fair Grounds having their

first view of a visiting dirigible. Mother was preparing to see this wonder,

too, but I interfered.

If you like to look for significances, you can find one in the

fact that Mother named me Vaughn Wilton, after two of her favorite actors,

Vaughn Glasser and Wilton Lackaye. Now I'm in show business, too. I've always

thought my names were too stagey, but while I've had to accept Vaughn, I've done

without Wilton.

Father was a rubber-research engineer, and we moved around

considerably as he worked in various plants throughout Ohio, Wisconsin, and

Pennsylvania. For about two years, while our permanent location was uncertain,

Mother, Bill, and I lived on my grandparents' farm not far from Akron, and I

went to a little country schoolhouse there.

Those were happy days. The farmers were dependent on one another

for entertainment and help in various ways, and this made for a neighborly

spirit. Every Saturday night the folks gathered at grandfather's house for a

get-together. I played the trumpet fairly well, my Uncle Fred and Mother got

tunes out of the violin and piano respectively, and a kid friend of mine, Hank

Scott, rattled on a snare drum. All the old and topical songs were sung, and

beautifully, too, and stories told, and jokes cracked. Around nine-thirty the

women retired to the kitchen and came back with big covered dishes of food which

each neighbor had prepared-- fried chicken, noodles, roast pork, ham, cakes,

pies. Dessert sometimes was a kind of fudge called "penuche" made of egg white,

sugar , nuts, and fruits. It was delicious.

The fraternal spirit was everywhere. If a woman was ill, the

neighbors took care of her children; if she made some quilts, the others shared

the work; if a man went into town, he loaded up with purchases for his

neighbors, too. Those days are gone. I'm sorry. Movies, radio, telephones, fast

cars, busses-- they have all contributed to making us less reliant on each

other, and much of the comradeship that used to be ours is no more. And we could

well use it now.

WHEN I was thirteen Dad moved us to Cudahy, Wisconsin, where

he was employed. He piled our belongings onto an old touring car, and us on top

of the belongings, and so we arrived in Cudahy, leaving a life I loved and always will remember.

Back of my mind there was the thought that it would be nice

to be a doctor, or something highly intellectual like that. But the trumpet

seemed to take up most of my spare activities, and it became pretty much of a

certainty that music was to be my career. I joined our Cudahy high school

orchestra, and the music director of the school took a special interest in me. I

played in several brass instrument combinations as well as in the school

orchestra, and so good was our instructor that we won a

number of prizes in state-wide competitions.

Before I could finish high school

in Cudahy, Father got a job in Jeannette. Pennsylvania, and we had to follow him

there. It was painful leaving Cudahy, for I had made many close friends

there. The sophomores at Cudahy High got out the usual yearbook, and many of my

schoolmates wrote in a parting message for me. It's a rather poignant experience

to read over those notes. I wonder where all those friends are now! One of the

girls in my class wrote this verse in my year- book:

There's a destiny that

makes us brothers,

None goes his way alone-

All that we send into the lives of

others

Comes back into our own.

Old, conventional stuff. But the truth's there. I think all of

us who were in that high school contributed to each other's lives. In Jeannette,

I got into the school orchestra, played at school dances,

tootled solos on various occasions, joined the glee club and a church choir. The

leader of that choir was Mrs. J. Hunter Smith, a vocal teacher. She told me I

had a voice worth training and gave me free lessons. That's how I made a start

in singing. She taught me for a year, and I became so interested in voice

training that I worked reasonably hard at it.

In Jeannette, too, I met Marian

Baughman, now my wife. Marian was the daughter of a local jeweler and a

member of one of the first families. Their home was a center for all the young

people, and every Friday night the rug was rolled up and the phonograph got

going. There were three girls and a boy in the family, so things were always

lively. Marian, at that time, took more interest in basketball than in boys. She

was a crack player and on championship teams. She was a tall, very attractive

girl with a boyish bob, and though she paid little attention to boys, they were

interested in her.

To me, Marian seemed a little snooty. I was not too

forward with girls-- shy and bashful, I heard myself called in those days-- and so

we didn't get acquainted for some time. Finally I asked to take her home from a

school dance one evening and she said yes. This surprised me as much as I was

surprised at my boldness in asking her. I found her nice and friendly, not what

I had imagined. From then on, we became good friends, but no more than friends.

It was a long, long time afterward before we realized that we were in love.

AFTER

my graduation from Jeannette High School, the Depression hit us, and hit my

family especially hard. Dad had a lot of stock in rubber companies which became practically worthless. From being a research. engineer he became a tire

salesman-- and selling on commission, too. He couldn't afford to send me to

college, and I went to work in a factory. After a year I saved up enough to enroll in Carnegie Tech in Pittsburgh as a voice major. To pay my way I worked in

local bands, taught trumpet to a few trusting pupils, and took over the church

choir when Mrs. Smith left for Chicago. Each day I traveled sixty miles to and

from Pittsburgh.

At the end of the first semester, I had lost twenty-five

pounds. The going was too tough. Around the same time I got an offer from a

professional band leader, Austin Wylie, to join his band and travel with it. I

felt miserable at the prospect of giving up my studies at Carnegie Tech. But

there was nothing else I could do, so I gave up everything and joined the band.

During the next few years I played with bands all over the

country, and Marian

and I saw each other rarely. Yet there was something in our friendship that held

us together. Marian had dates with boys, and I went out with girls, but when I

came home, she dropped all her dates and I forgot about the girls I knew, and we

spent the time together. Once, when I was playing Cleveland, Marian and a girl

friend from her college surprised me by a weekend visit. It was a time when the

band was out of luck and our engagement was in a Chinese restaurant which paid

off in meals. Marian and her friend thought we were making all kinds of money.

Maybe I gave her that impression in my letters. When they appeared at the

Golden Pheasant, they were dressed to kill-- trailing evening gowns, dance

slippers, etc. When I told them the sad truth, they quickly discarded the society wear, and we had a nice time.

Marian came out of college an expert in

personnel work. True to form, she was pretty ambitious. In the old days basketball dominated her, now it was personnel work, and the progress she could make

in it. Boys were still a very secondary interest. She got a job with the Gimbel

Brothers department store in Pittsburgh, where she directed personnel training,

and later became head of personnel with the Pittsburgh public utilities, quite a

big deal for a girl.

A dance band musician has to play in all sorts of places,

all over the country . Sometimes we had luck, sometimes we wondered where our

next week's salary was to come from. It was one long hard grind, fine for

experience, but telling on the spirit. I finally landed in Boston and met a

dynamic personality called Jack Marshard. Jack led bands and managed them,

specializing in society affairs. He must have played for everyone who was in the

Social Register in and all around Boston. Jack looked a right guy to me, and he

found something in me that he liked. He said, "Vaughn, why don't you quit

knocking around the country and settle here? I'll get you work."

Boston looked a

good place to settle in-- a large town, but quiet, too; big buildings and

excitement, if you wanted to be hectic, but nice shady streets if you wanted a

home life. I decided what Jack said made sense, so I left the band I was with-- it

was Larry Funk's then-- and came to Boston.

I began to dream of studying voice again and getting into

concert work. I did go so far as to take vocal lessons, but I discovered that

Jack had other plans for me; and when Jack has plans, he just has to go at them.

He shocked me by suggesting that I lead a band he was organizing for a Cape Cod

resort.

The thought of standing

in front of an orchestra scared me, and I backed out.

"Look, Jack," I said,

"I'm happy now. I got a job and I'm studying voice. I don't want to lead a

band."

To which Jack replied,

"Okay, just as you say. But I won't need you if you don't take this job."

So, with misery in my voice, I accepted. "What can I do?"

I said. "I need the money."

Jack laughed and told me

to try it a couple of weeks, and if I didn't like the work I could quit.

I couldn't sleep the night before I had to

get up in front of that band, but when I finally made it, I found it was not so

much of an ordeal after all. The people at Gables Casino, where I played, were

so nice, and gave me such a friendly welcome that I was able to get rid of my

shyness and fear.

After this I led bands for Jack and sang vocals. My brother

Bill, who learned to play the fiddle and sing novelty comic songs, joined me.

Being together gave us a feeling of home.

Marian and I heard from each other

regularly. She was very busy with her work; her name was on her desk, and on her

door, and she was pretty important, a career woman. Sometimes the thought of

marriage flashed through my head. But when it did I used to say to myself,

"What, me? A band musician? What have I got to offer a girl? Okay, I lead a

band, but there's a thousand guys who can do the same. I'm only a small guy,

and how far can a mediocre band leader go? So you earn a pretty good salary.

But-- you got to make a good appearance, you got to live in a decent place, you

got to do a little entertaining. No, you better forget about wedding bells."

In

the winter of 1940, Jack sent me to lead the band at the Dempsey Vanderbilt

Hotel in Miami. One night I had just got through playing a number when a long-distance

call came in for me from Marian.

"How are you, Vaughn?"

she said.

"Fine," I replied, "and

how are you?"

"I don't know," she

said. "Kind of disgusted."

The story writers tell us of those "moments" in one's life when

sudden revelations appear, when great changes occur, when a new world opens up.

The story writers are correct. That sort of moment was mine right then. It had

been almost twelve years since I first met Marian, and during all those years we

were coasting along on a pleasant friendship. Now, suddenly I was brought up

with a bang. No more coasting. This was the end of the run. I knew Marian was

not just a friend but the girl I loved and wanted to marry. The inadequate

salary? The mediocre band leader? All that didn't count a bit. Nothing

counted but the tremendous fact that I loved Marian.

I spoke into the receiver:

"I'm kinda blue, too." Then I said, "I love you, Marian, I always have. Why

don't you get onto a train and let's get married?"

There was a gasp at the other

end. She said, "Have you been drinking?"

I said, "No. I know how I feel, I know

what I want."

She said, "But-- you're crazy--"

"Look, Marian," I told her, "all

this does seem crazy, but I'll tell you what I'll do. I'll write you a letter

repeating all I've just told you, and I'll write a letter to your parents, too.

I'll send both letters special delivery."

We exchanged a few more words, in a

sort of dazed fashion, then said goodbye. That night I wrote the letters, one to

Marian, telling her all I felt, and then one to the Baughmans. I said to her

parents: "I'm writing to tell you that I've asked Marian to marry me, and I

also want to ask your consent. I promise I'll do my best to make her happy. I

hope you will approve. I know all the Monroes think the world of Marian. I hope

to hear from you soon. My sincere love and regards to all."

Next day came a wire from Marian: "I love you. Let me know when.

Earliest day I can get away

April first." Then on the next day I received a letter from the Baughmans,

giving us their blessing.

It was long after that I learned how that call from

Marian came about. Her brother and her roommate in Pittsburgh had fallen in

love, and that evening had gone out on a date. Marian had watched them leave,

had seen the brightness in their eyes, and had suddenly felt very much alone.

The name on her office door suddenly meant nothing; what did mean a lot was

that she was alone, and she became very blue. And without any other definite

thought in mind, just on an impulse, she called me.

I don't think it was just

a vague impulse. It was part of a design which neither of us recognized. I had

loved this girl for twelve years, wanted only her and no other, and finally

these circumstances came about to draw us together.

This was in February. As

Marian had wired me, she could not leave her job before April first, and it

would be impossible for me to leave my post with the band much before that date,

which was the end of the season in Miami. So, since Marian wanted a full church

wedding in her home town, we postponed our marriage till then.

A couple

of weeks afterward, Jack Marshard came down to Miami. We talked a little, then

he said, "Vaughn, you've had a lot of training playing in and leading bands. Why

don't we organize a big band, your band. I'll back you." It was a strange sequel

to what had happened between Marian and me.

I said, "Have you that much faith

in me?"

He answered, "I have."

I told him: "Then I have the same faith in you."

And we became partners in the new, unborn Vaughn Monroe Band. I hadn't yet told

Jack that Marian and I were to marry. Now I did, and wondered if it would make

any difference. Maybe he'd think a wife would mean an entanglement. But all Jack

said was, "I think that's swell. It's just what you need." That was a great

wedding gift that Jack proposed my own band, with my own name to it.

I arrived

in Jeannette two days before the wedding. Marian met me with the rings and the

wedding license-- I wanted her to choose the engagement and wedding rings, and

I didn't have time to get the license. This was the first time we had seen each

other since that telephone conversation.

WE WERE married on April second. Eight

days later the new Vaughn Monroe band was to open in Boston. And no rehearsals

had yet been held. The trip to Boston in our car was all the honey- moon we had

time for. Since I always fall asleep in cars, Marian did the driving. Before we

were five miles out of Jeannette, I was asleep, and I didn't wake up until we

arrived that night in Harrisburg. Marian said she didn't mind my sleeping away

the first hours of our marriage. She felt we had been together all our lives.

Through Jack Marshard's efforts the band got along well, and we finally came to

our present radio program. Marian originally helped to manage the band, but

after our children came-- we have two little girls, Candy (Candace) and Christy

(Christina)-- Marian retired to become a homemaker.

"Homemaker" and band-leader's

wife don't go together easily. Marian and I had decided to be together as much

as we could, and this meant traveling. And the traveling we and the kids have

done! We have changed innumerable diapers, heated innumerable bottles, and made

innumerable fellow-passengers miserable by our babies' squalling.

Lately,

traveling has become easier because I now own a plane and fly it myself. The whole

family can get in, and the children have developed the most casual familiarity

with planes. I've named the plane after them, "Cantina" (Candace and Christina).

We have established a home. It's in a New York apartment house,

but has enough rooms so the kids can run wild in it, if they want to. And

usually they do. The kids receive many gifts from my fans. Marian and I are

deeply grateful for these remembrances which come from persons we have never

met.

Fans are very warm-hearted people, but sometimes they can lose

themselves in their enthusiasms. I was playing at the Paramount Theater in New York a while ago when a

number of my fans clustered around me backstage. In some way, two got hold of

either end of my necktie and started pulling. I had begun to gurgle and turn

blue when ushers rescued me.

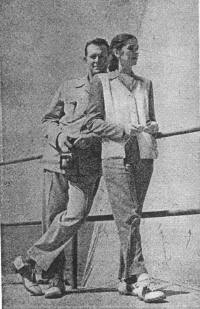

THE EIGHT years of our marriage have been happy years

for Marian and me. Our tastes run pretty much along the same lines, and this

makes harmonious living much easier. We both like sports. We often use the same

material and style for our suits and topcoats.

About meals we are casual. I

dislike routine in eating. I can't understand why people should have bacon or

ham for breakfast, but no other meats. If I feel like eating steak in the

morning, I have it. Or soup. And if I have a yen for cereal for dinner, why not?

Both of us believe in not being flustered or excited and in going along as

much as possible on an even keel. I admit it's a trick that doesn't always work,

but we make a hard try at it. Above all, we try to understand one another and

not indulge ourselves in resentments. It's really remarkable how things can

straighten out if you don't brood over them. The other day Marian said

reflectively, "It's a wonderful life we're having." Then she added very

seriously, "It has to be, to overcome what we're up against;"

Getting away from

the serious a little, one of the things I'm up against is that I have the kind

of voice which people either like or dislike. There's a guy out in Detroit who's

a disc jockey on WJBC. His name is Ed McKenzie. A very nice guy he is, but he

has fallen into the habit of calling me the "poor man's Caruso," the "voice with

the muscles," etc., indicating that he isn't quite in favor of my singing.

This

has been going on for quite a long time, and since he has a popular program, I

get a good deal of attention-- the wrong way. But a while ago there was

retribution. Ed had just finished his broadcast, in which he delivered himself

of the usual amusing crack at my voice, then went to his home, took off his

shoes, got into an easy chair, picked up the paper and settled down for a nice

restful hour, when a great chorus of voices rose outside. Ed jumped up and

looked out. A mob of high school kids was picketing his house and singing my

theme song. Bless the fans, even though they almost strangled me once!