Vaughn Monroe, the

$1,000,000-a-year music maker, leads a youngster's idea of a perfect life.

He's a childhood dream come true . . . an airplane pilot, a six-gun-shootin'

cowboy, motorcycle speed demon, model maker, and midget-auto driver all

rolled into one.

A FRIEND of mine, age 8, was

telling me not long ago what he plans to do when he grows up. It's a real

whiz-bang program.

"I wanna be an airplane

pilot, and a cowboy with a horse and pistols, and a motorcycle cop," he

said.

"Is that all?" I asked.

"'Course, I'll need a cowboy

suit, and a flyin' uniform. And a motorcycle, naturally, and an airplane."

"Wow!" I exclaimed. "Anything

else?

"Well, for fun I want a

midget auto, and some model trains, and a set of buildin' tools."

A pretty large order, I

figured, even for Superman. Never had I imagined that anyone could really

be an airplane pilot, a six-gun-shootin' cowboy, a motorcycle speed demon,

and a midget-auto driver all rolled into one.

It seemed even less likely

that the person who could measure up to this impossible ideal would turn

out to be a popular orchestra leader. I called it impossible, anyhow,

until I went up new England way recently and bumped into an individual

named Vaughn Monroe-- the walking, 6-foot-2 picture of my young friend's

dream come true.

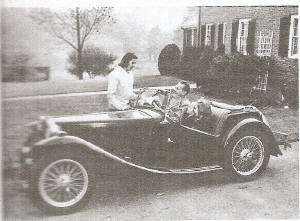

Not only is virile Vaughn at

home with a horse, plane, motorcycle, or roadster, but with everything

else an 8-year-old mind could concoct: the cowboy suits, uniforms, and

guns, the model trains, the workshop full of tools.

I decided that although Peter

Pan may be the most famous literary example of a boy who refused to grow

up, Vaughn Monroe is the greatest living proof that it's possible to grow

up and get all the things that every boy wants.

I had heard it said that Mr.

Monroe was the most successful singing-band leader on the American scene

since Rudy Vallee. I had also heard critics call his singing style an

"uncultivated barbershop baritone," and other equally insulting things.

However, when I visited his home in the sedate Boston suburb of West

Newton, Mass., I discovered a group of Monroe admirers who don't really

care whether he ever sings another note.

THESE are the kids in the

neighborhood of the comfortable 10-room house where Vaughn lives with his

wife, Marion (sic) [should be spelled Marian], their two

daughters, and a mixed-breed pup named Penny. To this bunch he's the local

Pied Piper, who leads a youngster's idea of the perfect life.

When I arrived there on a

recent Sunday afternoon, I found Vaughn in the back yard, his husky frame

draped casually in blue dungarees and a sport shirt. His own blond, pretty

children, Candace, 8, and Christina, 5, were entertaining a dozen

playmates of all ages.

"Daddy, " I heard Candy say,

"you promised to take everybody for a ride. Don't' forget, you promised."

Vaughn was in the middle of

so many kids that I was reminded of the old woman in the shoe, except

that, unlike her, he knew exactly what to do.

"Make yourself at home," he

told me, "while I perform my duties."

He went to the garage and

pulled a shiny black motorcycle, with fringed leather saddlebags, out from

between a big, well-polished limousine and a slightly beat-up station

wagon. One at a time, he gave each of the older kids a ride around the

block, holding them in his lap between the handle bars. Then we all

trooped across the street to a neighbor's garage, where I found that

Vaughn kept a low-slung midget roadster. This vehicle provided thrilling

excursions for all of the younger grade-school set. Afterward there were

hamburgers for everybody, cooked by Vaughn on the back-yard fireplace.

This, it turned out, he had built, himself. In fact, I learned later that

most of the gadgets around the house were built, remodeled, or improved by

him.

The back-yard circus which I

witnessed is a regular feature of life at the Monroes' whenever Vaughn is

at home between tours with his band. Not only is he a neighborhood hero on

the ground, but occasionally, as he shuttles back and forth between

engagements, his young followers catch a thrilling glimpse of him humming

overhead in his silvery twin-engine plane, which he pilots himself. To add

another touch of glory to the Monroe saga, they recently had the

breath-taking experience of watching him expertly rob a stagecoach, bust

up a couple of barroom brawls, and sock his leading lady in the kisser

while playing the hero of a bullet-spattered Western movie called

Singing Guns. Since last fall, for the first time, they've had Vaughn

Monroe on television.

It seemed like a good time to

try to separate Monroe the man from Monroe the $1,000,000-a-year music

maker, and find out how somebody goes about acquiring exactly what every

American boy considers the good things of life.

The way you do it, I learned

right away, is to start out by being a typical American boy. First, you

have to develop a taste for apple cider, doughnuts, popcorn, and roasted

chestnuts. These were the usual refreshments at Saturday night socials on

Vaughn's grandmother's farm in Cuyahoga Falls, Ohio. You have to take

naturally to swimming naked in the pond in summer, skating on the ice in

winter, and walking two miles to a one-room schoolhouse--with a snow

shovel to dig your way home on stormy days.

That was the kid of barefoot

country boyhood that Vaughn enjoyed with his brother Bill, who today is a

bass fiddle player living in Boston. Their father, Ira C. Monroe, was a

rubber engineer working at the Goodyear plant in Akron when Vaughn was

born. When Mrs. Monroe became ill during the flu epidemic after World War

I, the family went to live on the farm. After that there were camping

trips to the lakes around Akron, where Vaughn learned woodlore and

fishing, how to pitch a tent, and how to knock a can off a fence with a

.22.

VAUGHN'S musical career began

at the age of 11, when a friend of the family gave him an ancient,

corroded cornet which had been hanging in a woodshed, and Vaughn soaked it

in coal oil for week to get the valves to work.

"My folks almost put me in

the woodshed myself when I began to blast away on the thing," Vaughn told

me. "We didn't have a nickel to spare, but they decided--probably in

self-defense--to sacrifice a dollar a week for lessons."

By the time he finished

eighth grade, Vaughn was playing on key often enough so that his father

gave him a new trumpet for a graduation present.

I asked him what became of

the old cornet. "Follow me," Vaughn said, and led me into the pine-paneled

den. There, over the fireplace on a plaque, was the old-fashioned

instrument, shining like new with a coat of silver plating.

"A fellow named Edgar

Kaufman--I'd known him as a kid on the farm in Ohio--came to see me while

the band was playing in Columbus a couple of years ago," Vaughn said. "He

had this horn under his arm, and said he thought maybe I'd like to have it

back, because he'd gotten his money's worth out of it. Reminded me that

I'd sold it to him 25 years ago for a dollar, payable at ten cents a

week."

I admired the handsome,

mahogany-colored shield on which the cornet was mounted, and also the

other furniture in the dean--a pair of lamps made from two gold-plated

trumpets, an elaborate gun rack holding 6 rifles and shotguns, an

antique-looking cobbler's bench. "Made 'em all myself," Vaughn told me

proudly. "Come on down to the workshop."

IN a room in the basement I

found another one of Vaughn's boyhood dreams come true. "I always liked to

monkey around with a hammer and saw as a kid," he explained, "but, at the

same time, it looked as if there ought to be a faster way to get things

done."

Vaughn found the speedier and

easier way a few years back, when he bought himself a band saw with an

electric motor. He had so much fun with it that pretty soon everybody who

wanted to give him a birthday or Christmas present went out and bought him

another power tool. Members of the Monroe band, I learned, have chipped in

together and contributed a ripsaw, wood lather, metal lathe, drill press,

and planer, and a fancy instrument called a rabbeter, which can make the

edge of a board look like lace work. Vaughn now spends half his spare time

in the basement, knee-deep in sawdust.

I noticed also, a dozen or

more model trains scattered around the house, and asked Vaughn which of

the girls--Candy or Christy--like to play with them. "I like to play with

them myself," was the answer.

|

|

|

|

Mrs. Vaughn Monroe tells band leader

hubby to take

it easy. |

There's no stopping Vaughn when he's

making things in his home workshop. So his wife, Marian, has to

bring him lunch on a tray. |

Vaughn went on to explain

that when the Monroe band played its first big-time theater engagement at

the Paramount, in New York, in 1941, he found out, as he put it, "That you

can go crazy sitting around a dressing-room waiting for the next show to

go on--especially if you're doing five shows a day." So, to keep from

going batty, he took to carrying a model kit and some tools in his

luggage, and gradually assembled his present collection of miniature

locomotives, freight trains, and passenger cars.

In fact, Vaughn confessed

that his luggage, when on the road, calls for extra-strong porter and

band-boys to haul it around. This is because it contains enough dumbbells,

weights, and various other athletic equipment to fill a small gym. Vaughn

believes firmly in exercise, because he used to be a skinny kid who wanted

to fill out and look like a man. Today, as a 38-year-old singer, band

leader, and budding movie and television star, his problem is somewhat

different, namely, to keep the scales from bouncing much higher than 200

pounds when he steps aboard.

Back when he was still

scrawny and underweight, one of the ambitions he shared with most other

kids was to fly an airplane through the wild blue yonder. It wasn't until

1938, however, when he was a young singing trumpet player for a pair of

Boston society band leaders named Jack and Harry Marshard, that he

actually applied for a student pilot's license and began hedge-hopping

around the countryside.

No one objected to this hobby

until a couple of years later, when a tall, blond high-school sweetheart

of Vaughn's named Marion (sic) Baughman finally consented to marry

him. One of the first things she asked was whether flying was really

necessary. Vaughn pointed out that a band leader had to travel constantly,

and that if he had his own plane he could get home a lot oftener between

engagements. Marion (sic) decided to accept this argument.

Vaughn's first plane was a

bright yellow two-seater which he named Cantina, combining the names of

his two baby daughters, Candace and Christina. To show Marion (sic)

how safe it was to fly, he suggested one Sunday afternoon that they hop up

from New York to Bridgeport, Conn., to visit some friends. The weather was

beautiful, and they didn't start back until almost nightfall.

Marion (sic), herself,

described the return flight to me. "In that little plane, I felt as if I

were hanging onto a kite tail in the dark," she said. "I kept acting like

a back-seat driver, pestering Vaughn and asking him if he knew where we

were and which way we were going. He kept saying yes, yes, yes. Finally, I

asked him whether he'd ever made a night landing before. 'No, I haven't,'

he hollered. 'Now kindly let me alone so I can fly this airplane in

peace.'""

"After that," Marion (sic)

told me, "I just shut up and prayed."

They got down to earth

safely, and since then Vaughn has logged up 2,000 hours at the controls.

He has taken to collecting airplanes the way some successful men collect

race horses or chorus girls--never satisfied that the one they have is the

fastest and prettiest available.

SOON after buying the little

two-seater, Vaughn decided that it wasn't comfortable for business travel,

and traded it in for a 4-passenger ship--named Cantina II. A year later he

found he needed more speed and cruising range, and bought a twin-engine

5-seater--Cantina III. Then he thought it would be a fine idea to have a

ship that could carry most of the band members, while the baggage and

instruments traveled by bus. The result of this plan was Cantina IV, a

powerful 14-passenger airplane which it took two pilots to handle.

Vaughn's boyish enthusiasm

had carried him too far this time. Cantina IV turned out to be so big that

she couldn't use the landing fields in many of the small towns where the

band played one-night stands. Vaughn's bunch often found themselves

dropped at the nearest large municipal airport, with 50 weary miles left

to travel overland to the job.

Today he has compromised with

a smaller Cantina V, a two-engine plane which carries 6 passengers--or

used to, anyhow, until Vaughn had two of the seats torn out to make room

for extra fuel tanks and navigating equipment. Like a school kid hanging

coon tails and spotlights on his hot rod, Vaughn has filled Cantina V with

practically every instrument known to commercial flying., including a gyro

pilot, and instrument landing system, ground-control approach system, and

radio compass.

If anyone asks him about the

risks of flying nowadays, Vaughn tells them about the occasion last year

when Cantina V was grounded owing to bad weather, and he had to travel by

bus with the rest of the band from Richmond, Va., to Morgantown, W. Va.

Halfway through the trip the passengers smelled something burning. The

smell got worse. Finally the driver stopped and everyone made a dash for

the door. As Vaughn jumped out last, flames leaped from a rear wheel, and

in 20 minutes the bus was a charred mass of steel, with thousands of

dollars' worth of instruments and luggage cooked to a crisp inside.

"Nothing like that ever happened to me in a plane," Vaughn told me.

Vaughn's faith in airplanes

is, in fact, second only to his confidence in his own musical ability.

This he has in spite of the anti-Monroe propagandists who call him "old

Mellow Bellow," and "the voice with hair on its chest." Nor is he bothered

by the musical know-it-alls who complain Vaughn Monroe is becoming as

famous as Paul Whiteman, Fred Waring, or Bing Crosby, although he has

neither the original musicianship of Whiteman or Waring, nor the natural

vocal talent of Crosby.

Vaughn's dazzling glow of

self-confidence dates back to the year when his family moved to Cudahy,

Wis., just as Vaughn was about to enter high school. He found that in

Cudahy the school band was an even more important activity than the

football team. He proceeded to make a name for himself by becoming one of

the star brass players, and at 14 won the Wisconsin State trumpet

championship with a soul-stirring interpretation of a piece called

Pearl of the Ocean.

"We all went down to

Milwaukee for the contest," Vaughn recalls, "and John Philip Sousa was

there. He directed the combined high-school bands from all over the state.

I've never heard so much noise before or since, and I decided right there

that I was going to be a band leader like Sousa when I grew up."

That determination lasted

until Vaughn was 17. By that time the family was living in Jeannette, Pa.,

where Vaughn completed his last two years of high school, and where he had

his first date with Marion (sic). One evening he dropped in at the

Methodist church, picked up a hymnal, and joined the choir rehearsal.

Afterward, the director told him she needed another bass singer, and to

come regularly. That was the end of John Philip Sousa and the beginning of

the vocal ambition which has made Vaughn Monroe the most successful

singing band leader in business today.

NOT that Vaughn planned to

become a popular crooner. His goal was to make himself a great opera

singer or a star of the concert stage--a Lawrence Tibbett or a John

Charles Thomas. He decided to go to college and study music, but since

there was no money for higher education in the Monroe bank account, he

first got a job as a mold-man's helper in the tire plant where his father

worked. For a year Vaughn wrestled heavy tire molds all day and played

trumpet in a dance band two or three nights a week.

He enrolled at Carnegie Tech,

in Pittsburgh, the following year, and signed up for voice lessons, piano

lessons, harmony, theory, languages. In order to learn to move gracefully,

he took up fencing.

This program was supposed to

produce a great American basso for the opera and concert stage, but,

unfortunately, the plan collapsed in 1931 because of lack of funds. Vaughn

left college to go on the road with a dance orchestra, and spent the next

four years in constant travel.

In 1935, the Marshard

brothers, whose lucrative specialty was providing music for the coming-out

parties of millionaires' daughters around Boston, offered Vaughn a job. He

took it for two reason. The first was that he liked Boston, and wanted to

make his home there. The second was that he hadn't forgotten his ambition

to become a first-rate singer instead of a second-rate trumpet player. He

settled down to his do-re-mi-fa's once more at the New England

Conservatory of Music.

The Marshards, however,

decided that Vaughn would make a presentable band leader for their deb

parties, and put him in front of a 6-piece unit. During the winter of

1940, while Vaughn's group was playing at a hotel in Miami, Fla., Jack

Marshard and a New York band manager named Willard Alexander dropped in

one night to check up on things. Alexander had heard that Vaughn could

warble a few notes, and had a hunch that a singing band leader might be a

novelty for the public. It was decided that night that Vaughn would put

away his trumpet and be groomed as a big name in the music business.

His reaction to this stroke

of fortune was to put in a long-distance call to Jeannette, Pa. When

Marion (sic) answered the phone, she wasn't sure whether she was

listening to a poor connection or whether Vaughn was talking from under a

bar stool. Finally she figured out that he was trying to ask her to marry

him. Being a cautious girl with business training, she told him to put it

in writing. She still has the letter.

Once married, the Monroes'

first home was a $20-a-month cottage near a roadhouse outside Boston

called Seiler's Ten Acres, where Vaughn Monroe and his orchestra were

introduced to an unenthusiastic public. Vaughn's take-home pay amounted to

$25 a week during this first summer, even with Marion (sic) doing

the bookkeeping for the band.

To make things worse, Jack

Marshard--who was since killed in an auto crash--decided that as a popular

jazz singer Vaughn was strictly from the New England Conservatory of

Music. In other words, nowhere. He hauled a recording machine up to

Seiler's, and a vocal coach from New York named Ticker Freeman, who set

out to cut Vaughn's overdeveloped tonsils down to microphone size and turn

his booming basso into a domesticated baritone.

This program worked so well

that a year later the RCA-Victor company signed the refurbished Monroe

voice and band to a recording contract. The band played its first big date

the Paramount Theater in New York not long after, and was soon playing in

hotels and dance halls all over the country, and broadcasting a weekly

radio show on the CBS network

Being a mere band leader,

however, had never been Vaughn's idea of a great career. He decided that

if he couldn't become an opera singer right away, why not try something a

little different--namely, horse opera? If he couldn't be Faust or Figaro,

maybe he could at least give Hopalong Cassidy a run for his money. There

was only one drawback: He didn't know how to ride a horse.

Vaughn set out to remedy this

shortcoming with his usual determination. The members of his band began to

wonder why their leader disappeared every afternoon, in whatever city,

town, or whistle stop they happened to be playing. They never guessed that

Vaughn had suddenly gone crazy over horses, and was patronizing the local

riding academy.

Also as a subtle part of the

build-up, Vaughn began singing more and more Western ballads, in an effort

to persuade his public that he was a sure-'nough rootin'-tootin' cowhand

from the lone prairie. It got so bad a couple of years ago that you

couldn't' get near a radio or juke box without hearing him blasting out

some melancholy Western ditty like "Cool Water."

AT THIS point Hollywood was

convinced, and Republic Pictures, which have probably produced more

oat-fed films than any other studio, dressed Vaughn up in a sombrero and

pistol belt and turned him loose on an old-fashioned thriller called

Singing Guns. They gave him a couple of songs to sing, a pretty

heroine to slap around before the final kiss, and a double-crossing

so-and-so to exterminate with his trusty 6-guns.

Vaughn is proudest, however,

of the way he got along with the range hands and wranglers on the set in

Arizona, where the picture was made. "They looked at me at first like I

was the world's lowest from of animal life--a band leader trying to act

like a cowboy. When they introduced me to my horse, everybody seemed

surprised that I knew which side to get up on. Then I showed them I could

do a running dismount, without breaking a leg, and after that everything

was O.K."

Today Vaughn Monroe is no

longer just an entertainer, but is engaged in a large-scale business

enterprise. In addition to being president of Vaughn Monroe Productions,

Inc., the corporation which reaps the $1,000,000-a -year rewards of his

band business, he also has an interest in the movies in which he will

appear, owns a small music-publishing company, and is a major partner in a

mammoth country restaurant outside Boston know as The Meadows.

This last investment occurred

4 years ago, after Vaughn put in a bid to buy Seiler's Ten Acres--the same

spot where he once earned $25 a week. He offered the owners $50,000, but

the place was snatched up by a rival band leader. Vaughn's answer was to

pitch in with the Marshards and another partner, buy out a turkey farm in

a superior location on a main highway, and build on it a $500,000

ranch-style dine-and-dance establishment seating 1,100 guests. The Meadows

did $120,000 of business in its best month this year.

It has been estimated that

all the Monroe enterprises together roll up a gross of about $2,000,000

yearly. Yet, in spite of the rich, full life he leads today, some of

Vaughn's friends told me that he actually is a frustrated person, and that

he has never been happy since he gave up studying for grand opera and

switched to what some people call his "million-dollar monotone."

I questions Vaughn on this

subject, and am happy to report that there's no truth to the rumors. In

the first place, he feels that most of his youthful ambitions have been

fulfilled. The schoolboy who wanted to ride a motorcycle, drive a snappy

automobile, and fly an airplane now does all three.

Nor does Vaughn believe for a

minute that he ruined his classically trained voice by singing popular

tunes. He points to Ezio Pinza, who went form opera to Broadway to

Hollywood, and Dorothy Kirsten, who switched from opera to radio duets

with Frank Sinatra, and back to opera again.

It wouldn't surprise Vaughn

in the least--thought it would certainly surprise everyone else in the

music world--if he turned up on the Broadway stage in a show like South

Pacific. It wouldn't even surprise him if the gold curtain of the

Metropolitan Opera parted some evening and revealed his manly frame to the

occupants of the Diamond Horseshoe. "I can still sing the prologue to

Pagliacci," he told me proudly.

I DECIDED that probably the

only boyhood ambition which Vaughn had actually outgrown was the one we

all remember from early childhood, when we were told that some day we

could be President. But I discovered later that I may have been wrong

about that, too.

I learned that a couple of

years ago--on April 15, 1948, to be exact--a member of the legislature in

Vaughn's adopted state of Massachusetts invited him and his orchestra to

perform for the assembled lawmakers in the State Capitol. The idea was

that the Monroe organization was a credit to the commonwealth, and

deserved this unusual form of recognition.

It was quite an occasion.

Both houses of the legislature assembled in the State House, and Vaughn

and the band arrived in a bus, followed by 1,000 cheering school kids,

some of whom got by the guards and swarmed onto the floor. The band played

a few numbers, and Vaughn sang "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling" from the

speaker's rostrum.

In discussing the unique

performance with me, Vaughn pointed out that politics and showmanship are

very much alike. "I don't see why an experienced band leader wouldn't make

a darned good public official," he said.

I've been mulling over this

point of view, and I wouldn't be surprised, some day soon, to hear that

Vaughn Monroe has descended by airplane in the middle of a crowed of

cheering fans, played them a chorus of "Stars and Stripes Forever" on his

trumpet, sung the prologue to Pagliacci, and announced his

candidacy for the highest office in the land. Anyhow, if the kids in his

neighborhood were old enough to vote, I'll bet he could at least get

elected mayor of West Newton.

THE END